Sun and wind: Designing for east Idaho microclimates

Published at | Updated at

Editor’s note: This is the final article in our series on the principles of landscape design, in which we have focused on correcting common design flaws while accounting for east Idaho’s climate.

The secret to a thriving garden is not fighting the regional climate but rather grasping the “grand master” of design: context.

Context is crucial in design, shaping how your garden interacts with its surroundings, your home’s architecture, microclimates, soil type and the high-desert landscape of east Idaho. Effective design should feel integrated with the environment’s aesthetics.

Every garden has its own special nuances — be pros or cons — but the beautiful thing about gardening is that there are so many plant species and cultivars that there is always something that will work there. Even those spots that seem like cons to a garden design can be charming with the right understanding of its microclimate and the right paring of plant for that place.

Microclimates are small areas within a larger environment that experience different weather conditions compared to the surrounding USDA zone. These conditions, such as temperature, moisture or wind patterns, can be influenced by the area’s specific location, nearby structures and vegetation. As a result, a microclimate may be hotter, windier or cooler than the rest of your yard.

These variations can occur throughout the year or be seasonal. You might discover a sunny corner where tulips burst into bloom much earlier than you would expect, or a cozy shaded nook where frost hangs around longer than in other areas. These delightful surprises can transform parts of your yard into entirely different growing zones.

Designing a garden with microclimates involves manipulating small-scale environmental factors like sunlight, wind and moisture to create diverse, tailored habitats for plants.

Key strategies include using south-facing walls for warmth, planting hedges for windbreaks, installing water features to increase humidity, and utilizing mulch to regulate soil temperature. Observing your landscape throughout the seasons helps identify frost pockets and hot spots, allowing for strategic plant placement.

Key principles for microclimate garden design include:

Identify existing conditions: Spend time observing light, shade, wind exposure and soil drainage across your property at various times of the day and year.

Leverage thermal mass: Use walls, fences and rocks to absorb heat during the day and release it at night, creating warmer spots for tender plants.

Create windbreaks: Protect sensitive plants from harsh and drying winds by planting hedges, trees or installing fences, or place them in those areas of the yard that already have those features.

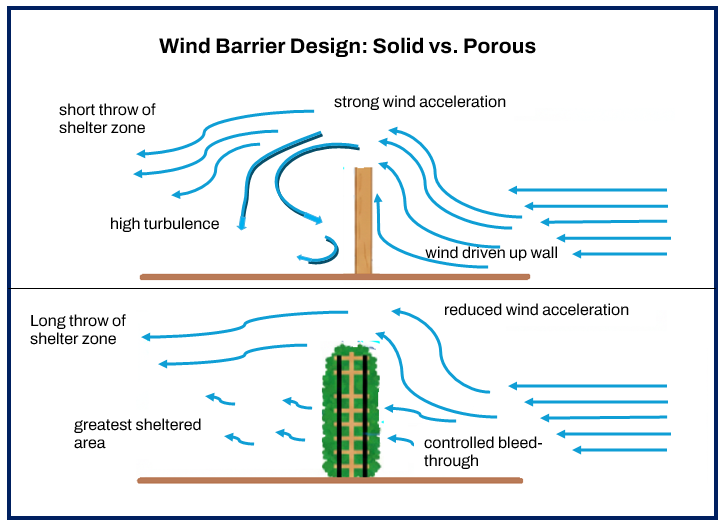

Gardeners will get more benefit by not “fighting” the wind so much as re-directing it. A solid barrier does not actually protect as much area on the leeward side as a slightly diffuse barrier. This is because a solid barrier causes eddies from the low pressure directly on the leeward side.

I use diffuse barriers, like a slat fence, for a narrow space. A staggered hedge will also work to slow the wind and lift it, rather than trying to stop it cold, creating a much gentler environment for your plants.

For a complete explanation on windbreaks in the Inland Northwest see this free PDF from Extension.

Pick the right plant for soil conditions: Sandy, heavy, dry or wet, there is an ornamental plant for that soil. You can also make modifications like improving drainage in wet, low-lying areas by building raised beds or using mounds to protect plants that dislike “wet feet.”

Layering for shade: Use taller trees and shrubs to create shade for cooler, moisture-loving plants underneath, mimicking a forest structure.

Microclimates can be shaped by a variety of factors, both natural and man-made. For instance, structures like brick walls, patios, and driveways soak up sunlight and release warmth long after the sun has set. This results in cozy, warm spots perfect for early-blooming beauties like crocuses and daffodils. Later in the season, this overnight heat retention can help with plants that need warmer night temperatures like tomatoes and peppers.

On the hand, shaded areas — especially those nestled beneath thick trees or alongside taller shrubs — tend to stay cooler and may even face more frost. These spots can delay flowering which might mess up your design goals unless you take it into account beforehand and use it to extend the bloom time in your yard of those plants.

Water features like ponds or backyard fountains are also fantastic contributors to microclimates. They help stabilize temperatures, keeping nearby areas warmer on chilly nights and cooler on hot days. Obviously, the closer you are to a larger body of water the bigger the effect.

Elevation adds another layer of interest to your garden’s temperature dynamics: hilly terrains are often noticeably different in temperatures. For example, a low dip in your yard might serve as a frost trap while a gentle slope can promote enough airflow to keep frost from settling.

South-facing slopes warm up sooner in the year but are also drier — notice the native vegetation difference between north and south slopes on the benches and foothills near you. North-facing slopes hold the snow longer, slowly releasing the water as plants begin to break dormancy.

With a little exploration and understanding of these wonderful microclimates, you can cultivate a vibrant and diverse garden that flourishes in its unique way.

Happy gardening!