Former Rexburg man remembers uncle, who oversaw construction of the Teton Dam

Published at | Updated atEDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second in a series of stories highlighting the 50th anniversary of the Teton Dam Disaster. Read our first installment here.

IDAHO FALLS – Richard Robison was 13 when he saw the collapse of the Teton Dam about 15 miles northeast of Rexburg. His uncle, Robert Robison, oversaw its construction in the 1970s, and its failure affected him for the rest of his life. Fifty years later, Richard hopes to transform one of the worst civil engineering disasters in American history into a cornerstone of Idaho’s future.

Robert Robison was the last man on the crest of the dam at the moment of failure on June 5, 1976. As an employee for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Robert was involved in the construction of Willard Bay — the dam separating the fresh water from the salt water in the Great Salt Lake — more than a decade earlier. He’d worked on projects in Colorado and Nevada after that before moving to Rexburg in the early 1970s.

Richard, 63, lives in Cincinnati, Ohio, today, but grew up in Rexburg. He was about 9 years old when his uncle came to town to begin construction on the Teton Dam.

“I can still remember how exciting it was when dad told us Uncle Bob was moving to Rexburg,” Richard says.

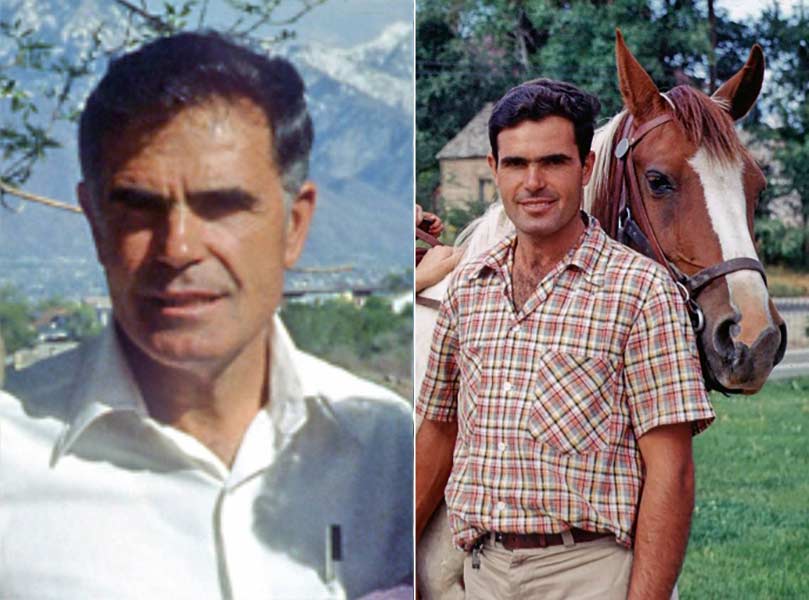

Richard describes his uncle as a handsome man with a look similar to that of Rock Hudson or James Garner. Robert had a commanding presence and was intelligent and well-spoken, according to Richard. He and his siblings deemed him the favorite uncle because he’d spend time with them and take them fishing.

Although the Bureau had approved the Teton Dam project in 1964, political tensions had stalled its construction. Despite concerns about its design, funding was secured in 1971, and the project moved forward.

RELATED | Remembering the Teton Dam’s contentious backstory 50 years after its collapse

Richard, a retired engineer who has studied the Teton Dam for 40 years, attributes the project’s approval to one major factor.

“It was just hubris and overconfidence in their design,” he says.

Between 1950 and 1979, more than 40,000 dams were built across the country. The Bureau of Reclamation had built many of them, none of which had failed.

“The design they’d chosen for the Teton Dam was a pretty standard embankment design,” says Richard. “The design group didn’t feel like they needed to make any significant changes to compensate for the difficult geology.”

At the time, Richard says engineers considered the design a cost-effective and efficient way to build a dam, and it earned a major engineering award. That award was rescinded after its collapse.

Robert had expressed concerns about the dam’s design from the beginning. Since the designers and contractors were siloed in different buildings, they rarely communicated with each other. Robert’s feedback fell on deaf ears, and as the project manager, he had no other choice but to move forward with construction.

Richard has fond memories of riding in the car with his dad to see Robert at the Teton Dam site and get a behind-the-scenes tour.

“I remember standing at the top of the canyon looking down and Robert showing us the massive excavation that was going on to put in the foundation,” Richard recalls. “The enormousness of the excavation … was just unbelievable. It was the coolest thing an 11-year-old boy could see.”

In subsequent tours, Richard and his dad got to see the diversion channel being built along the Teton River and watch the reservoir rise as the dam was built.

The collapse and the aftermath

Hours before its collapse, on June 5, the reservoir was nearly filled to capacity, and the dam was operating without a functioning outlet works or spillway gate. Without a mechanism to control water flow and pressure, the dam’s failure was imminent.

“Bob was fairly certain at 9 a.m. that morning that the dam was going to collapse,” says Richard.

Robert and several other contractors were on site that day. He, along with John Calderwood, Owen Daley and others, tried in vain to plug seepage holes on the downstream face of the dam. Richard says his uncle ended up being the last man standing on the crest of the dam.

“They were pushing what they called riprap — large boulders — into the whirlpool that developed. They hoped it would plug up the pipe,” says Richard.

Minutes before its failure, the group realized their efforts were futile and were forced to evacuate.

RELATED | The Teton Dam broke 44 years ago today. This man was sitting on it when it happened.

At 11:55 a.m., the dam burst, destroying about 3,000 homes and tens of thousands of acres of land. Eleven people died, along with 13,000 head of livestock, according to news reports at the time.

Robert’s home was among those affected. Once the floodwaters had permeated the area, Richard says his family’s driveway became the control center for the Bureau of Reclamation.

“I was feeling a lot of despair, and then my uncle showed up. They set up a trailer and radio systems,” Richard recalls. “(Robert) was completely professional in doing his job to manage the crisis.”

In the weeks that followed, Richard says Robert and his family received death threats.

According to Richard, Robert saved hundreds of lives and successfully fought to ensure the Bureau of Reclamation compensated those affected.

The total cost in damages was around $2 billion — more than $11 billion in today’s dollars.

Once the cleanup was finished and reparations had been made, Richard says his uncle expected to begin rebuilding the Teton Dam, but it never happened. Instead, the dam site was closed, and all the contracted employees lost their jobs. Richard says the tragedy became a “national embarrassment,” and major dam construction projects nationwide ceased.

“Our country lost its stomach to go out and build major dams like that again,” Richard says.

Congress passed the Reclamation Safety of Dams Act in 1978. It authorized the U.S. Secretary of the Interior to modify, repair, or replace Bureau of Reclamation dams to ensure structural safety.

Robert continued working for the Bureau for decades, but Richard says he carried the weight of the tragedy for the rest of his life. Although Robert never talked about it, Richard says it affected him until his passing in 2018.

“It traumatized him, but it never impacted his productivity or his role as a father or uncle,” says Richard. “He passed away at age 93, so that’s a long time to carry that weight.”

Reshaping a legacy

Fifty years later, the Teton Dam collapse remains one of the most studied civil engineering disasters worldwide. A proposal to rebuild it co-sponsored by Idaho Senator Kevin Cook, R-Idaho Falls, in 2025, is gaining momentum and Richard is one of its most ardent supporters.

One of the reasons Richard became an engineer was because of his uncle and he sees the dam’s reconstruction as an opportunity to complete his uncle’s “unfinished business.”

“It was meant to be a promise to the Snake River Valley for water security and irrigation resilience. Fifty years later, it represents unfinished business and an unkept promise,” he says.

In a conversation with EastIdahoNews.com last week, Cook cited a 1996 study conducted by the Bureau of Reclamation. The report says that the Bureau had the necessary resources to build the Teton Dam back then and that it could be rebuilt safely in the same location.

“The Bureau had the necessary information available (in 1976) to develop an adequate defensive design. A safe dam could have been built at the site utilizing design concepts that were known at the time,” the report said.

During a presentation with water stakeholders in August 2025, Cook cited data that showed rebuilding the Teton Dam was the most cost-effective of any other proposed water storage project. That’s due, in part, to the infrastructure that’s still in place.

It would also store about 350,000 acre-feet of water — the most capacity of any other project.

“It gets the most bang for the buck,” says Richard. “So that really is the cornerstone project.”

He hopes to see the proposal gain support as he continues to advocate for it. Richard says he’s planning to return to Rexburg this summer to commemorate the disaster’s 50th anniversary.

WATCH OUR INTERVIEW WITH RICHARD ROBISON IN THE VIDEO ABOVE.