April Neal explains the many roles dispatchers play to help who need help

Published at | Updated at

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story is part of a five-part series examining the lives of law enforcement and emergency responders in the Pocatello/Chubbuck area. Read Part 1 on a school resource officer here. Read Part 2 on volunteer firefighters here.

POCATELLO — An effective dispatcher is part psychologist, part internet investigator and part advice nurse, all packaged neatly in the as an expert customer service provider.

Pocatello Police Department dispatcher April Neal hits all those nails on the head, according to dispatch lead Stephanie Harris.

“Her empathy, her passion, her work ethic, her ability to multi-task,” Harris said, listing the attributes that make Neal good at her job. “Her ability to remain calm in the heat of the moment, in the chaos. Having that ability to separate herself emotionally from what you’re dealing with because you’re dealing with life and death.”

RELATED | Here’s why Pocatello PD Officer Kevin Nielsen has the ‘best job in the department’

And thanks to the life-and-death nature of her job, the work can be full of extreme highs and lows — sometimes daily.

Looking back on Neal’s four years on the job, the shifts that come to her mind the quickest have to do with officer-involved shootings. That is when all her skills are put to the test.

“It’s definitely a tough job,” Neal said. “People maybe don’t realize it, but there’s a lot of stress.”

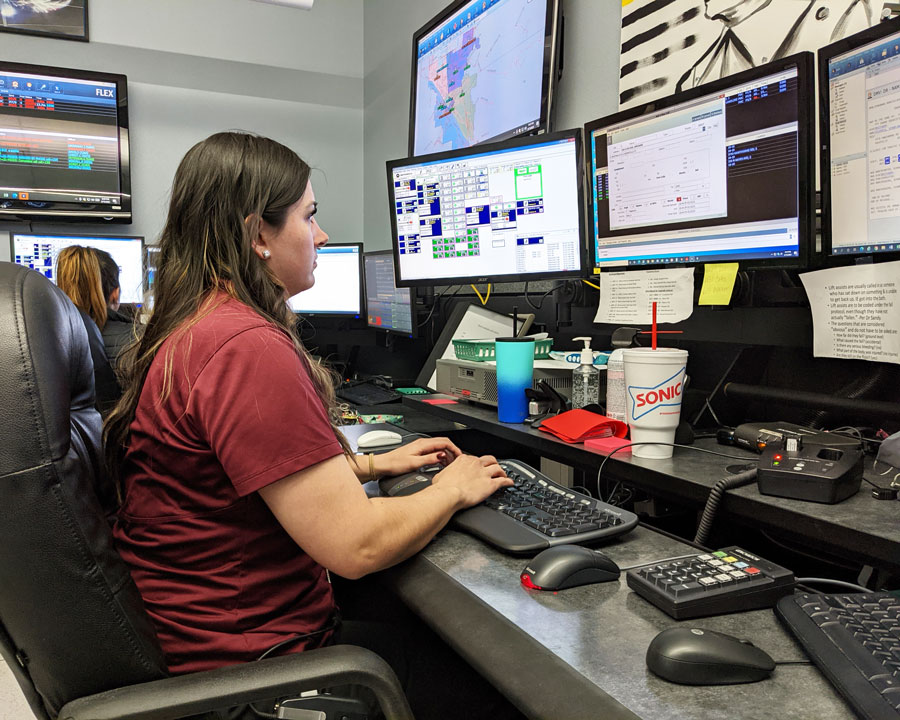

Surfing through different computer programs, dispatchers must provide officers with all pertinent information in the quickest manner possible. And there’s no room for mistakes.

One slip or misspoken word could send backup or emergency medical providers to the wrong place, or send them ill-prepared to the correct location. Missing an alert in a suspect profile means officers in the field will not get information like the suspect’s affinity for concealing weapons or a history of violence with law enforcement. Allowing emotion into her voice could lead to elevating an officer’s emotions in tense situations.

That same relaxed and calming demeanor is needed to handle every call because, as Neal said, “people don’t call us on their best of days.” Being calm and reassuring relaxes 911 callers, who are often victims of or witnesses to a crime, and guides them to provide additional information that they may not have been able to under stress.

Dispatchers must also have a strong grasp on local geography as well as the technical know-how to find information with limited assistance.

EastIdahoNews.com got to sit in on a shift with Neal, and watching her work was awe-inspiring.

RELATED | Volunteer fire department bringing help and heroes to community

At one point, an out-of-state call was received requesting a welfare check. The caller did not have an address, phone number or even last name of the party for which they were requesting a check, only a general location and brief description. With what little information she had, Neal found the address, phone number and even a picture of the person in question.

Neal’s ability to use all the tools at her disposal is impressive. But the ability of the entire dispatch center to work together, in a sort of unchoreographed waltz, is even more so.

A crew of no less than three dispatchers is on duty at any given minute in Pocatello, each with a specific assignment — taking emergency calls, taking non-emergency calls, dispatching PD, and dispatching fire and ambulance.

But when, as Harris says, “the ‘shift’ hits the fan,” the group moves in unison.

“It is its own little dance. It’s like a wheel. We’re all working together,” Neal said. “We always keep one of our ears open — room awareness is big, because if (one dispatcher) is taking a medical call, then I (can) dispatch her ambulance. That way, she can focus on her call.”

Dispatchers are also trained to provide medical assistance as units are en route to an emergency.

Neal and her fellow dispatchers can walk a caller through CPR, along with many other potentially life-saving emergency medical applications. Doing so is part of a 32-week on-the-job training program new dispatchers go through.

For Neal, though, eight months wasn’t enough to make her comfortable.

“I feel like you should always be learning something. Every day,” she said. “I was comfortable about two years into this job. There’s always that call that you’ve never taken before — people go four or five years before they have a working house fire. It’s never just the same old in and out. Every call is different.”

And although dispatchers might never leave their desks, they are still very involved in the care of callers.

“We are not on the scene physically, but we are there,” Harris said. “Our voices are there. Our talents are there.”

For Neal, an Idaho State University grad with a degree in sociology, it isn’t getting callers the help they need that proves tough, though. It’s hanging up to let responders take over.

“The most difficult part (about this job) is not knowing what happened to certain people, like on medical calls,” Neal said. “We only talk to them until the ambulance gets there. Sometimes we find out (what happened) if we have an ambulance crew call, whether they survived or not. Not knowing what happened, there’s a lack of closure. But you have to keep moving on because people will always need our assistance. They’ll always need 911.”