Grow your skills: Introducing our garden design series

Published at | Updated at

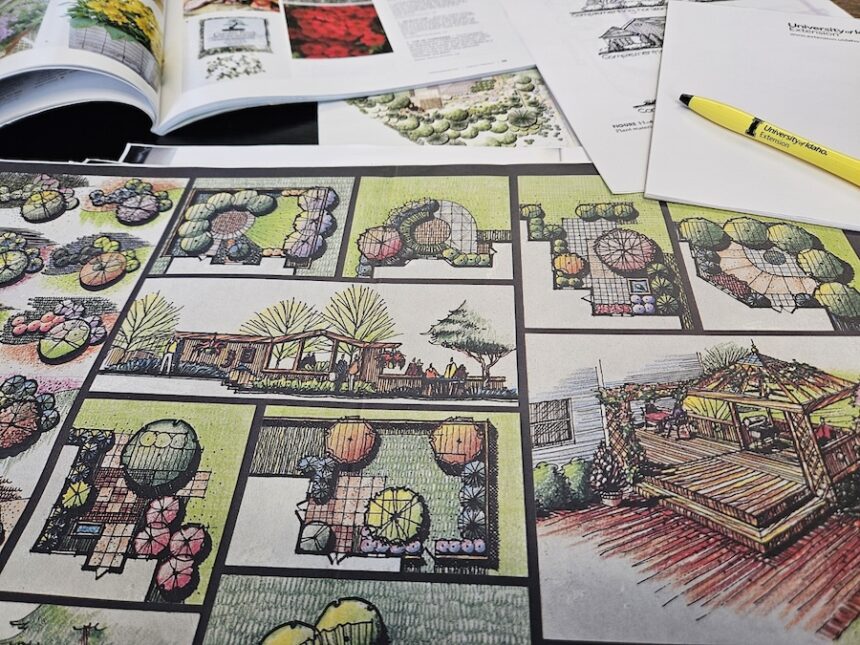

Editor’s Note: In this series on the principles of landscape design, we will be focusing on correcting common design flaws while accounting for east Idaho’s climate. Each week until February, we will take a detailed look at a couple of principles and how you can apply them to your property, elevating its aesthetic.

As we move into the winter and the plants go dormant, so too do some of our ideas on what to write about for you east Idaho gardeners. But there is plenty to think and plan for regarding our yards and gardens even when the snow and winds start blowing. For the next eight weeks we are going to discuss the principles of good design, applied to our local yards and garden conditions.

Recently, I was reminded how a small physical adjustment will change the aesthetics of the whole. My recently purchased house had old aluminum frame windows. With new windows, in black trim to contrast the cream-yellow brick, the whole house has a different style. While you might not have the budget or desire to do a whole landscape make-over, even small changes using design principles can have a big impact.

Besides the design itself, additional planning for a landscape includes a site analysis, what does your site have that you can capitalize on or views into or out of the property that you want to screen. Think about these things as we move through this series. The following is a brief explanation of each of the common design principles. Each section will be treated more fully in the next articles.

Unity and contrast

Having a set palette, group of plants, or hardscape material will help you build unity from the beginning of a new yard. You want to build continuity and a sense of place.

In practical terms achieving Unity means limiting your choices. Instead of using five different types of decorative rock, stick to just one—perhaps a locally sourced, neutral river rock or lava rock—and repeat it throughout all your beds. Instead of using a dozen different kinds of shrubs, select three or four resilient varieties, and plant them in mass groupings, and use them both near the front of the house and along a back fence. This creates a visual “thread” that ties the whole landscape together, even though you might have diverse areas like a xeriscape bed and a vegetable patch.

Unity is especially important in high-desert gardening where our plants face difficult growing conditions. We may feel tempted to through everything at the nursery into our garden to make up for the lack of lots of green vegetation that we see in gardens of more hospitable climates. But using a consistent foliage color palette, particularly those with silvery, drought-tolerant foliage (like Russian Sage, Rose Champion, Artemesia), immediately imparts a calm, harmonious feeling, making the garden feel deliberate and whole, rather than a collection of random parts. This shared sense of belonging is the essence of unity.

Contrast or Variety: Contrast is the necessary complement to Unity. If everything in your garden is the same size, texture, and color (perfect Unity), the result is monotonous. Variety introduces visual interest by intentionally juxtaposing elements—like placing a fine-textured fern next to a coarse-leafed hosta. Or using a few ‘variety’ plants with our core plat palette in the front yard, and a completely difference set of ‘variety plants with the same core palette in the back yard. This contrast keeps the eye engaged, but it must be used sparingly to avoid chaos.

Rhythm and repetition

Repetition: As with music, repetition can be used tastefully, a phrase of notes is repeated throughout a song, or a chorus between versus. Skillfully using repetition means you pay attention to the negative space or emptiness around each unit. A line of shrubs or trees evenly spaced with a gap between them can be a nice addition to a driveway, lane or path. Think of the repeated upright spikes of ‘Karl Foerster’ grass running along a fence line. The feeling and sense of design can be varied with the size of the gap. Repetition used without connecting to another design element risks creating monotony, like that simple kid’s song replayed in rapid succession.

Again, rhythm is easily understood when recalling music. Rhythm is the deliberate use of complex repetition or a pattern. Rhythm in the garden is created by the recurrence of an element, (plant or material like fencing) or multiple elements which guide the eye along a path or border. Take the following picture, The foreground has some small dark green bushes in groups, probably boxwood along with some lighter green plants boarding the path and a few shrubs trained or grafted on standards (trunks) This repetition creates a visual beat that moves you through the space.

Scale and proportion

An easy one to comprehend and a hard one to make yourself do. In my opinion, designing a landscape is the hardest medium to work in because it grows and changes after you are “done”, as it should, but you have to be disciplined in your choice of location for plants. The longer lived the plant, the more conscious and deliberate your placement. Putting that cute evergreen in the planting bed by the house in a spacing that looks good now usually means it is way too close to a window, door, sidewalk etc. for its future size. Let’s get away from the “that is someone else’s future problem” mentality so we can all enjoy better design and functionality in the years and yards to come.

Function: I put function here with scale and proportion because I often see dysfunctional paths, sitting areas and similar issues using the yard and garden associated with scale and proportion- more than any other design element. Plan your main grass walkways, paths or sidewalks wide enough for at least two people to walk side by side. Let there be nice sitting areas and benches in the garden. If there are you will find yourself looking at the garden through the window while you stay inside or are only out there when you’re working. There has to be functional sitting, structures, or entertainment areas to help draw you outside.

Balance and simplicity

Balance can be exact – formal and symmetrical – or freeform, plainly by visual “Weight” or mass. This type of planting is asymmetrical but still balanced.

Take the repetition example of a tree lined driveway. If the facts and conditions of the site in question allows for trees on one side but not the other, then we can look to balance the trees with shrubs or perennials that are suited to the site or skip plants if needed and use boulders on the other side.

Simplicity is more than emptiness. A bed can be done such that each plant has lots of space around it before the next plant. If your personal aesthetic tends to this organized, spaced-out look that’s fine, that can be an example of using simplicity and repetition. But consider the alternative of simplicity in plant material used; limiting yourself in the type of plant to two or three but using a lot of those two or three species or cultivars, planted massed together. For example: two spring blooming perennials, two summer blooming perennials and two fall blooming perennials. The bed would have a total of six plant types, simple when viewed all together and only two (or three) blooming together, BUT in such quantity to really be noticed and pleasing. Add to that contrasting foliage and good color choices and you have a real showpiece.

Form and shape – transition and line

We generally use Form and Shape when referring to plant material. Form describes the 3D structure (like upright, or weeping), while Shape can be the basic geometric shape of the plant, it’s leaf, or flower. Line defines the edges of planting beds and the paths that move us through the garden. Transition is how smoothly we move between different lines, or areas, creating flow rather than abrupt stops. Using these well can define your whole garden’s feel.

Color and texture

In east Idaho, we must think about Color beyond the summer bloom time. Foliage colors such as blue-greens, silvers, deep greens, and golds provide year-round interest and don’t rely on flowers. This is especially useful in shaded areas where flowering isn’t as abundant as in part to full sun. We can also make better use of spring flowers and bulbs to increase the bloom period in the yard.

Texture refers to the individual leaf size and shape. Thinking of how light plays on the plant surface is another way of understanding texture: fine (like ornamental grass or Honey Locust leaves) or coarse (like a large rhubarb leaf). The whole architecture of the plant can also have a texture to it. This is especially noticeable when the landscape is covered in winter snow, evergreens tend to appear as a fine texture, something like birch or weeping trees are a somewhat medium texture. While the branch structure of hackberry or catalpa is distinctly coarse. Contrasting Color and Texture is essential for depth or richness of the design.

Emphasis and focal point

You can bring emphasis to an important part of the yard such as an entry way or sitting area by framing it with plants or adding a little formal symmetry. A Focal Point is the spot in the garden that immediately draws the viewer’s attention. This could be a dramatic accent plant, a beautifully crafted piece of hardscape, or a unique gate.

Every well-designed space needs one key area to command attention, otherwise the eye wanders aimlessly. In our region, a hardy, structural element that looks great in the winter as well as the growing season is a good choice for a focal point. Another option is framing a good view beyond the property if you have that luxury in your yard.

Context

Context is the grand master of all principles; it is how the garden space relates to everything around it—your house’s architecture, microclimates around structures and the neighborhood, your soil type, and most importantly for us, the wider, high-desert landscape of Southeast Idaho. Your design should feel integrated, not like a separate bubble. Ignoring the surrounding views, climate, and existing structures means ignoring the ultimate principle of good design. This takes skill but it can be done, you can have a floriferous and attractive landscape that has the flavor of the native flora and natural design of the region.

Context also goes beyond design into the maintenance and long-term health and vitality of the plants selected. Good design shouldn’t make maintenance tasks extra difficult such as mowing or edging in tight corners for excessively squiggly bed lines. Or using microclimates around your house to your advantage.

As you notice it’s often hard to define and describe how you use a principle without using another one. That is because they all tie together and need to be used together for full effect.

If you haven’t had experience with design in another medium, you might feel overwhelmed. Don’t let the quantity of principles hinder you. Pick the most obvious or the easiest problem and apply the corresponding principle to it, you will be surprised how big a difference it makes to the whole yard.