Eastern Idaho experiencing hottest winter on record; Pacific Northwest gripped by ‘unprecedented snow drought’

Published at | Updated at

POCATELLO – Last Wednesday, Portneuf Valley residents woke up to an uncommon sight this winter – snow.

This was the same day that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) program held a news briefing on the “unprecedented snow drought” that is gripping the Pacific Northwest, as well as much of the Intermountain West.

By the time the webinar had started in the afternoon, nearly all of Pocatello and Chubbuck’s morning snow had melted.

During the briefing, reporters from Idaho, Washington and Oregon heard from a variety of experts on the scale of the current snow drought, and how it could affect the rest of the year.

Unlike most droughts, the current one has not been driven by a lack of precipitation. Instead, it’s been caused by record-setting warm temperatures.

RELATED | Eastern Idaho shatters records with warmest December in 85 years

RELATED | Record-breaking temperatures set on Christmas Day in three eastern Idaho cities

The hottest winter on record for eastern Idaho … so far

According to the National Weather Service’s Pocatello office, this winter (December, January, and February) is, so far, the hottest winter on record for eastern Idaho.

In Pocatello, the average temperature of this winter is currently 35.7 degrees, and Idaho Falls’ is 33.3 degrees, compared to their normal average temperatures of 26.6 degrees and 21.9 degrees, respectively. In Burley, this winter’s average temperature is 37.9 degrees, and its normal average is 29.2 degrees.

This means that Pocatello, Idaho Falls, and Burley are 9.1, 11.4, and 8.7 degrees above normal on average this winter. In Pocatello, the average temperature is currently 2.1 degrees higher than the winter of 2014 to 2015, the previous warmest on record.

According to Tim Axford, a meteorologist at the NWS Pocatello office, it doesn’t look like temperatures will cool off enough for eastern Idaho to instead see its second-warmest winter on record by the end of February.

“For us to drop down into a number two spot, we would need to see a pretty dramatic drop off … we would need to see a pretty good Arctic outbreak of cold air,” Axford said.

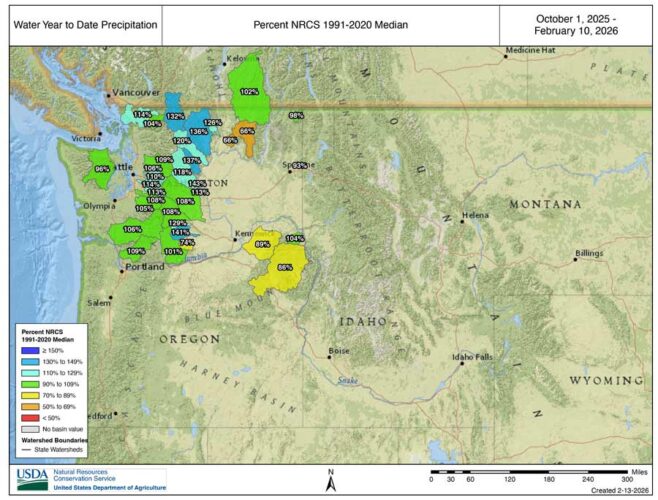

And Idaho is not alone in experiencing a record-setting warm winter. According to Deputy State Climatologist Karin Bumbaco of the Washington State Climate Office, this is the warmest start to a water year (October to January) on record in her state. And State Climatologist Larry O’Neill with the Oregon Climate Service said that November to January was his state’s warmest three-month span on record as well.

Eastern Idaho’s temperatures have gotten hotter over time

EastIdahoNews.com previously reported in December that eastern Idaho had been receiving southerly winds, bringing up warm air from California, Nevada and Arizona.

While Axford said overall, temperatures have been warming over time, he would hesitate to say that this year is representative of what future winters will look like.

“Generally, we can’t really make conclusions based on one day, one event, one season,” Axford said. “(You) get these outlier years that can really stand out. Now, looking at the data overall, there is a warming trend that is occurring. So in general, yes, temperatures have been warming, but this one year, I would hesitate to say, is leading to something else.”

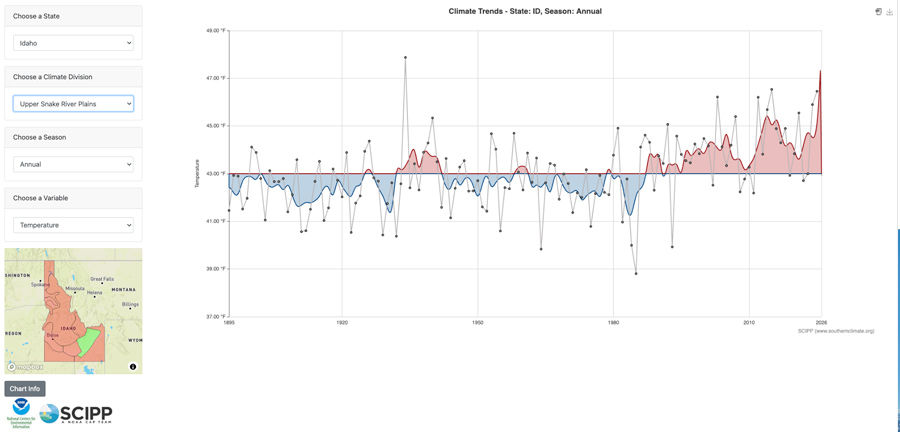

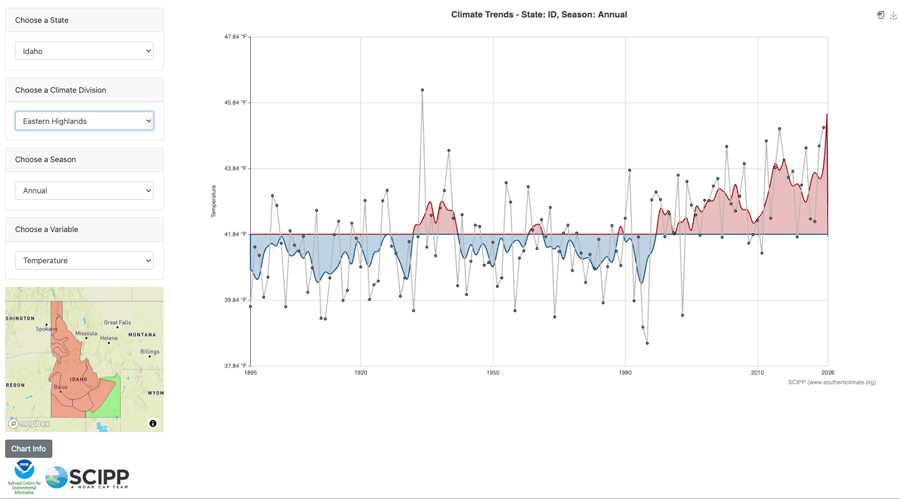

The Southern Climate Impacts Planning Program, a NOAA research team funded by its Climate Program Office, has mapped this general warming trend on its Historical Climate Trends website.

Eastern Idaho is split between the Upper Snake River Plains and Eastern Highlands, with both charts showing a clear warming trend. The horizontal line depicts the region’s long-term average, with the five-year moving average shown in blue or red, depending on whether it’s below or above the historical average.

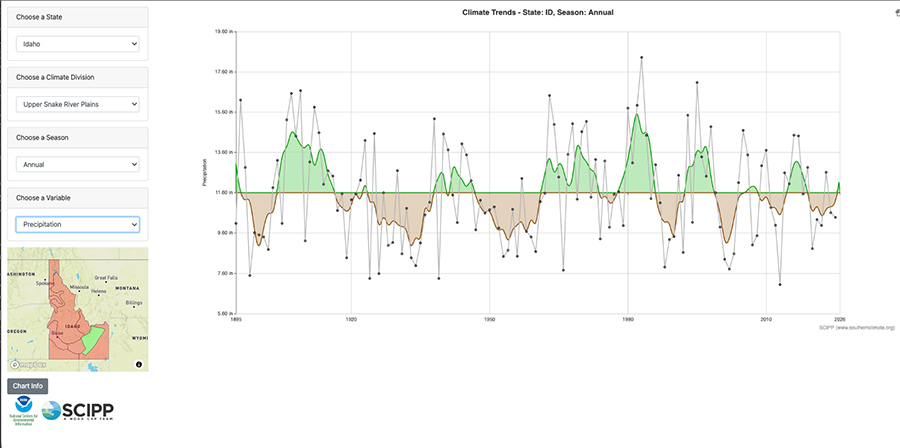

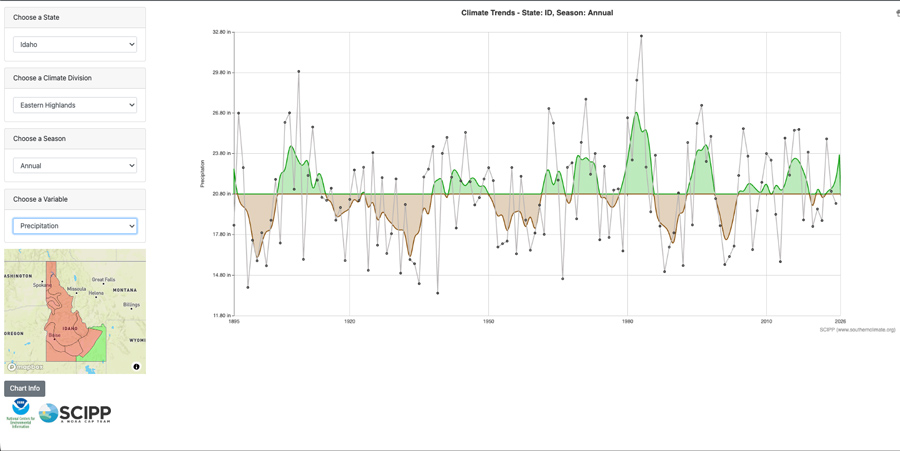

This contrasts with Idaho’s precipitation levels, which don’t show a clear trend in either direction over time.

Snow drought driven by temperature, not precipitation

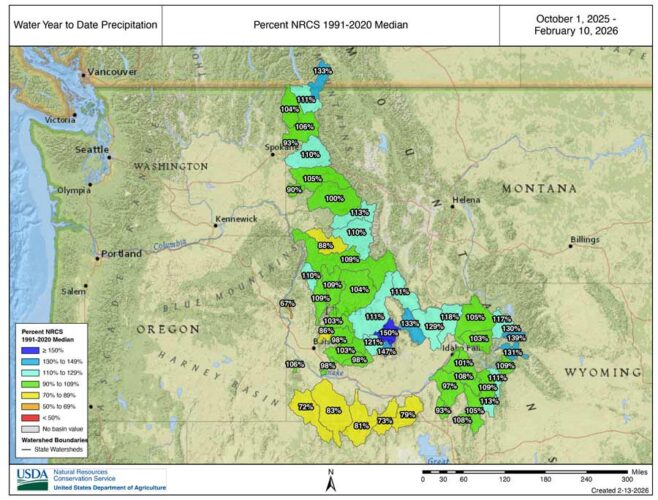

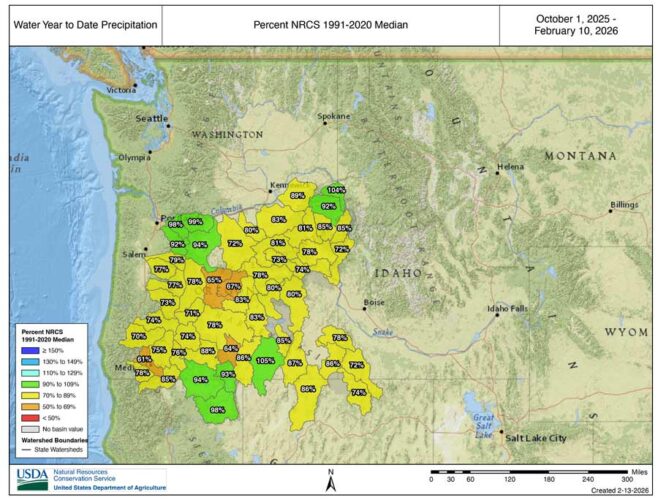

While this winter has been unusually hot, precipitation has fallen at a normal rate.

“When I (look at precipitation levels), most of our stations are at or above normal,” said Mark Dallon, service hydrologist at the NWS Pocatello office.

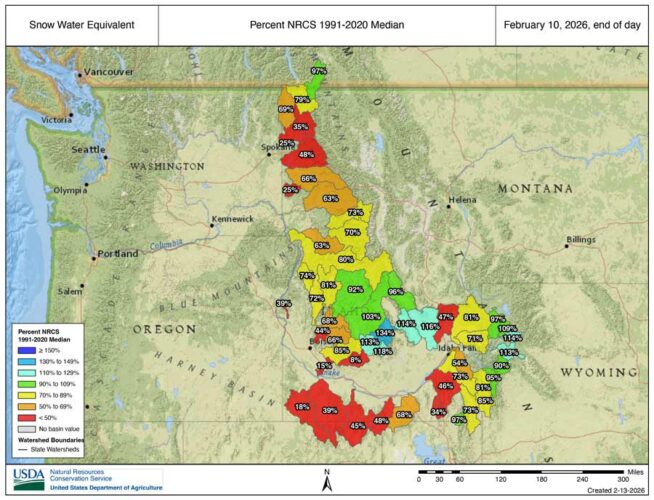

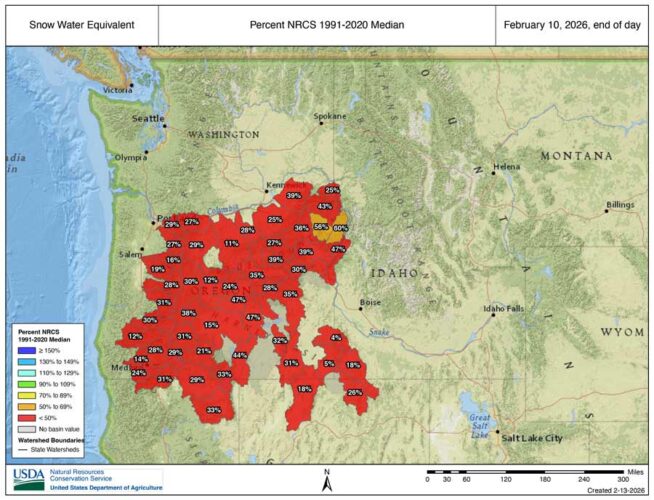

But these precipitation levels stand in stark contrast to the Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) levels at these stations. SWE represents how much liquid water would result if the snowpack melted instantaneously, and both it and precipitation are measured in “percent of median,” meaning that 100% is the median.

For example, the Portneuf subbasin has received 97% of its median precipitation since the start of the water year on Oct. 1, but its current SWE is 46% of the median. Dallon said this is because the Portneuf sits at an elevation low enough that, when precipitation falls, it’s taken the form of liquid rain due to the high temperatures.

This divergence between SWE and precipitation in lower-elevation sites is highly unusual, Dallon said.

“I’ve been tracking this stuff for 20 years. I’ve never seen this much of a difference,” he added.

To view SWE and precipitation levels in an interactive map, click here.

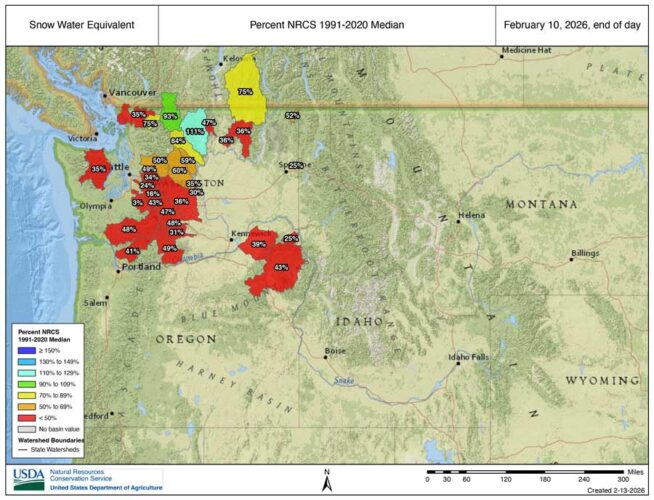

How’s Oregon and Washington doing?

The snowpacks of Oregon and Washington are in worse condition than Idaho’s. During the webinar, O’Neill said that a late-season snowpack recovery is “really not likely,” based on the amount of precipitation Oregon normally receives.

“Even with the snow that we received in the last weekend, it only bumped us up a little bit, and we’re still, as a statewide average, experiencing our worst snowpack on record,” O’Neill said.

Bumbaco expressed a similar sentiment, stating how unlikely it is for Washington’s snowpack to recover.

“Every basin in Washington, except for the upper Columbia, needs more snow than we’ve seen in 90% of our historical records to get to normal by April 1,” Bumbaco said.

David Hoekema, hydrologist at the Idaho Department of Water Resources, spoke in the webinar for Idaho. He noted that while some basins are in good condition, that’s not the case for others, noting that North Idaho is experiencing its “worst drought on record.”

“There’s very little chance of having a normal snow pack this year,” Hoekema said.

Idaho’s higher elevation has put it in a better position

While both Oregon and Washington both have tall mountain peaks, Idaho’s mountain ranges are generally at a higher elevation.

“Even though there are some high peaks like Mount Rainier and others in Washington State, on average, the mountains are not quite as high,” said Russell Qualls, Ph.D, Idaho State Climatologist and an associate professor at the University of Idaho.

Qualls explained that this is the main reason why Idaho’s snowpack is in a better situation than Oregon and Washington’s.

“(The) stations that have a decent snow pack, relative to historical averages, are all high elevation stations … and those stations, because they’re higher, have colder temperatures,” Qualls said.

Currently, one of the strongest snowpacks in all of Idaho, Oregon and Washington is in the Big Lost subbasin, in south-central Idaho, at 131% of median SWE.

While Idaho is in a better position, Qualls also noted that Idaho’s lower elevation sites are very much in line with Oregon and Washington’s.

What could this mean for the future of Idaho’s water system?

While the experts who spoke in Wednesday’s webinar cautioned against viewing this winter’s high temperatures as being caused solely by climate change, they also expect to see similar winters in the future.

“This one winter doesn’t necessarily tell us that it was caused by climate change. But … from our projections, we know that the winters in the coming decades are going to be much more like this,” O’Neill said. “(What) we can’t model is how we’re going to respond to it, how we adapt to it or even if we’re going to mitigate it.”

Qualls said that if the warming trend continues, it will shorten the window of time when snow pack is able to accumulate.

“You might have October and March, kind of becoming warmer, so that the snowpack, even in the higher mountains, begins to accumulate later in the season, and then begins to cease accumulating or beginning to melt earlier the following spring, and the net effect of that is to have a reduced snow pack. Even in those higher areas,” Qualls said.

Qualls noted that there will still be years where temperatures are colder than the historical average, and snow pack has a long enough window to accumulate.

“We have individual years that go up and down, but we have this persistent trend where we’re going from cooler temperatures to pretty persistent warmer temperatures, and those warmer temperatures on that … running average, are tending to increase,” Qualls said.

And at a certain point, the question isn’t if Idaho needs to adapt, but how.

“Let’s set aside the issue of long-term climate trends … (The) mid-1980s going back nearly 100 years, we had cooler temperatures. Since then, we’ve had warmer temperatures. … You can’t really go 35 years under conditions that impact the crops you grow or the amount of water that you need … without adapting at least somewhat,” Qualls said.

This weather-related story is brought to you by Pony Express Car Wash, Idaho's premier express car wash destination, renowned for its commitment to exceptional service and quality. Voted the No. 1 car wash company in Idaho for three consecutive years, we pride ourselves on delivering an unparalleled experience for every vehicle and customer. Our state-of-the-art facility utilizes name-brand soaps and cutting-edge equipment to ensure your car receives the ultimate clean. Established in eastern Idaho in 2019, Pony Express is proud to be a locally owned and operated company that caters to the unique car washing needs of our Idaho Friends and neighbors. We invite you to experience the difference at Pony Express, where your satisfaction is our ultimate goal.