How Memorial Day became a national holiday and why 3 Idaho inmates joined the army after WWI

Published at | Updated at

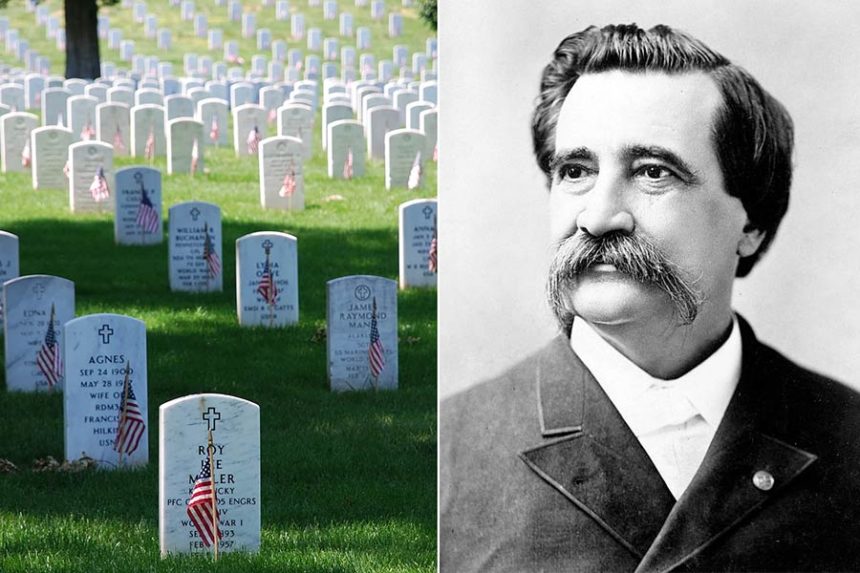

IDAHO FALLS – General John Logan had decades of military experience when he gave the order that set the stage for the creation of Memorial Day.

It was May 30, 1868, more than three years after the end of the Civil War, when General Order 11 created a day of remembrance for those “who died in defense of their country.”

“(It) is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet church-yard in the land,” the order says.

RELATED | Locals celebrate dedication of new veterans memorial near Rigby

Logan, a native of Illinois, was 21 when he first joined the U.S. Army in 1847. He served as a second lieutenant in the Mexican-American War and went on to serve in the Civil War under General Ulysses S. Grant. During the Battle of Belmont — Grant’s first major battle as brigadier general — Logan’s horse was killed. Logan would be wounded during the Battle of Fort Donelson on Feb. 15, 1862.

Simultaneously, Logan had also been involved in politics. He got his start as a county clerk in 1849. As a member of the Illinois House of Representatives, he reportedly helped pass a law that prohibited all African-Americans, including those who had been granted freedom, from settling in the state. Ironically, Logan resigned a seat in Congress on April 2, 1862 to join the fight against slavery in the Union Army. He entered the Union Army as Colonel of the 31st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which he organized.

“He was known by his soldiers as “Black Jack” because of his black eyes and hair and swarthy complexion, and was regarded as one of the most able officers to enter the army from civilian life,” a Wikipedia page about Logan says.

Years after the end of the deadliest war in American history, Logan was now the second Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic. General Order 11 set the stage for establishing what eventually became Memorial Day.

“In this observance, no form of ceremony is prescribed, but posts and comrades will in their own way arrange such fitting services and testimonials of respect as circumstances may permit,” the order says. “It is the purpose of the Commander-in-Chief to inaugurate this observance with the hope that it will be kept up from year to year, while a survivor of the war remains to honor the memory of his departed comrades.”

Logan resumed his career in politics and went on to secure a Republican nomination for vice president. He and his running mate, James Blaine, were defeated by Grover Cleveland and Thomas A. Hendricks.

Logan was 60 when he died on December 26, 1886.

The day he helped create has since been expanded to include veterans of any American war. In 1971, Congress officially declared Memorial Day a national holiday.

The last line of the order Logan signed contains a plea to the media about remembering the sacrifice of America’s veterans.

“He earnestly desires the public press to lend its friendly aid in bringing to the notice of comrades in all parts of the country in time for simultaneous compliance therewith,” it says.

Through the years, EastIdahoNews.com has frequently highlighted stories of veterans, living and dead, and their accomplishments during times of war. Today, we’re highlighting three veterans who enlisted in the military following World War I after serving time at the Old Idaho Penitentiary in Boise.

Idaho inmates join the army

On April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson officially declared war on Germany. The conflict had already been going on in Europe for the last four years as America remained neutral, but a rise in German submarine attacks on U.S. merchant ships led to a rise in American casualties.

Earlier that year, British cryptographers, according to the National Archives, deciphered a telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German Minister to Mexico. What has since become known as the Zimmermann Telegram was a proposal offering American land to Mexico in exchange for an alliance against the U.S.

Wilson, who had been re-elected the previous year on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” was now calling on America to join the global conflict.

“The wrongs against which we now array ourselves are no common wrongs; they cut to the very roots of human life,” Wilson said in a joint session of Congress. “The world must be made safe for democracy.” Americans must fight “for the rights and liberties of small nations” and “bring peace and safety to make the world itself at last free.”

Not long after, the Selective Service Act went into effect, which required all men between the ages of 21 and 30 to register for a possible draft. The law included those who were incarcerated.

While most inmates were not activated for military service, the federal government launched a nationwide campaign encouraging those unable to enlist to invest in the war effort by buying liberty bonds. A display at the Old Idaho Penitentiary shows many inmates bought liberty bonds and donated money to the Red Cross.

A parole board did allow three inmates housed at the penitentiary to join the army upon their release. Those inmates were Burrell Tiffany, Ira Lee and Russell Clark.

“Lee and Tiffany survived the war, but it is unclear what happened to Clark,” the display says.

EastIdahoNews.com was unable to find any information about Tiffany, but did find a few sparse details about the other two.

Genealogical records for Lee indicate he was born in Bear Lake, Idaho. He was 22 when he died in San Mateo, California months after joining the army.

As for Clark, not much is stated about his service record. He reportedly served with the 154th Depot Brigade, 2nd Company at Camp Meade, Maryland. In the penitentiary’s Facebook post about him in 2020, officials say he held the rank of private.

Clark served about a year at the Old Idaho Penitentiary and was pardoned on March 1, 1918. He was arrested on forgery charges in February the year before.

“At the time of his arrest, Clark worked for Union Pacific Railroad. Two months prior, while working for the Oregon Shortline Railroad, he obtained a check made out to another man, then signed their name and cashed the check for $40,” the post says.

Clark was discharged from the military on Dec. 10, 1918. It’s not clear what he did after that, but the Facebook post says he was admitted to the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers on August 22, 1932 in California.