Shoshone-Bannock author sheds new light on history and legal battles over Indian hunting rights

Published at | Updated at

FORT HALL — A debut book by Fort Hall native Cleve Davis is reigniting discussion about the history, cultural meaning and legal battles surrounding Indian hunting rights — topics that wildlife and land management agencies remain reluctant to address publicly, despite their ongoing significance to Tribal sovereignty.

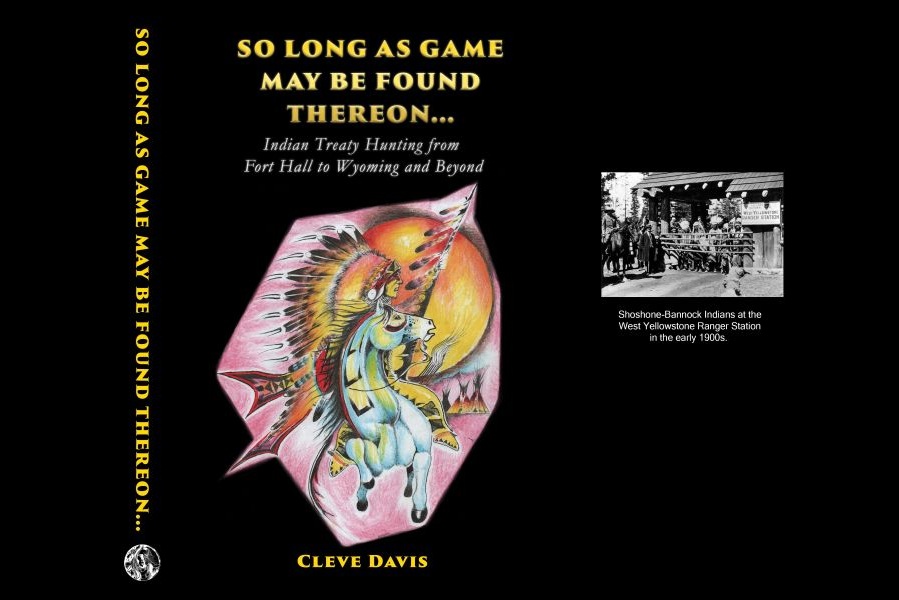

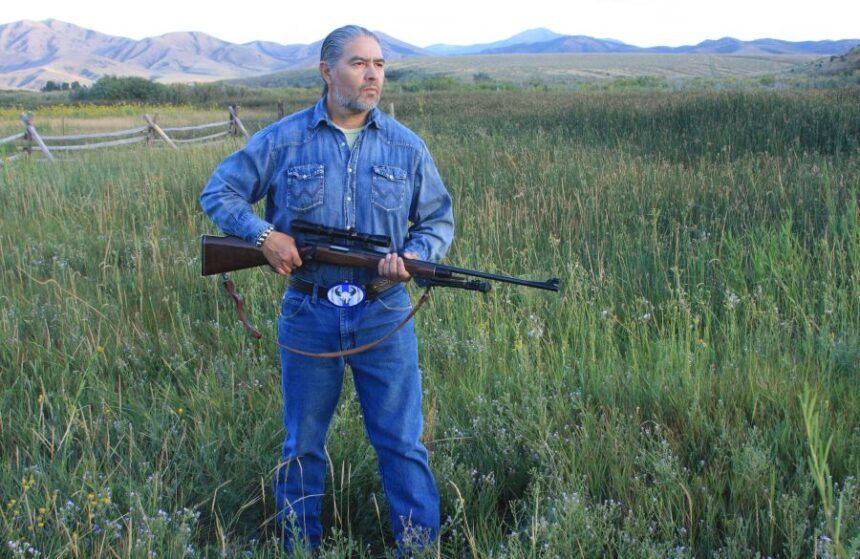

Davis, a rancher and enrolled member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes who holds a Ph.D. in Environmental Science, recently published “So Long as Game May Be Found Thereon… Indian Treaty Hunting from Fort Hall to Wyoming and Beyond.”

The book follows three years of intensive research, drawing on historic treaties, U.S. Supreme Court cases, Tribal teachings and Davis’ own life journey.

He said the book examines the history and ongoing legal struggles involving the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation and the Crow Tribe — each of which holds off-reservation treaty hunting rights.

Because the Shoshone and Bannock words for “hunting” also include fishing and gathering, the book explores salmon fishing rights and other traditional practices that remain central to Tribal life.

Davis hopes his own tribal members and all hunters in general will better understand a struggle that is often overlooked or misunderstood.

“I want people to confront uncomfortable truths about American history, colonialism and the ongoing fight for justice,” he said.

Life’s defining moments inspired a desire to write

Davis said the project grew out of a difficult chapter in his life. As a young man “on a bad path,” a counselor encouraged him to learn about his Tribe’s ceremonies and teachings. This guidance helped him become a more spiritual and grounded person.

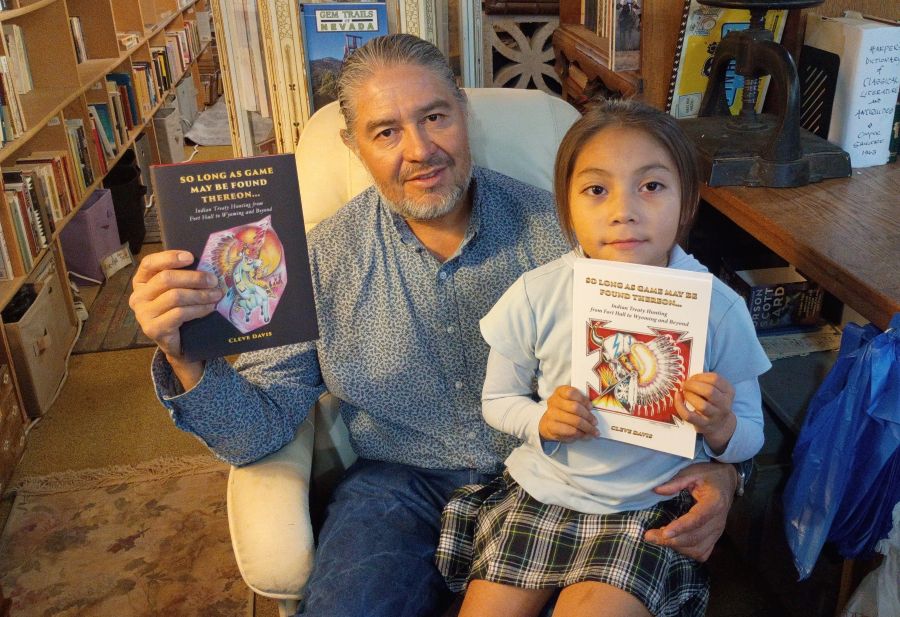

Years later, while applying to enroll his daughter, Isla Rain, in the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, he began researching his family’s ancestry as part of the enrollment process. As he gathered the records, he realized the importance of preserving this history so that future generations would understand where they came from and the heritage they share.

He immersed himself in his roots, teaching himself both the distinctly different Shoshone and Bannock languages and exploring how Indian hunting rights have shaped the experiences of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and other Tribal nations over the years.

“I’ve always known my Shoshone-Bannock heritage, with both parents enrolled in the Tribes. Yet it wasn’t until I began to explore the history of my ancestors and the origins of my people that I grasped the depth of my identity,” he said.

Through that research, Davis discovered he is a direct descendant of John Race Horse Sr., the Bannock man at the center of the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court case Ward v. Race Horse — a landmark decision involving off-reservation treaty hunting rights in Wyoming.

“We need to know and remember where we came from,” he said. “It’s important to learn about our families and their knowledge, our culture and apply it to today’s world.”

Examining treaties and landmark court cases

Growing up on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation, where hunting and fishing shaped his upbringing, Davis delves deeply into the off-reservation treaty-hunting rights retained by the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, and the Crow Tribe.

Davis writes extensively about the impacts of federal assimilation policies, which discouraged traditional hunting, imposed Christianity, and attempted to transform Native hunters into farmers.

Central to his research is the 1868 Fort Bridger Treaty, which under Article IV states that the Shoshone and Bannock Indians “shall have the right to hunt on the unoccupied lands of the United States so long as game may be found thereon.”

Davis also analyzes Ward v. Race Horse, a 1896 U.S. Supreme Court that challenged treaty-hunting rights in Wyoming.

The 1868 Fort Bridger Treaty — why it matters

The 1868 Fort Bridger Treaty was an agreement between the U.S. government and the Eastern Shoshone and Bannock peoples. In it, Tribal leaders agreed to live on a reservation, but they intentionally kept important rights, including the right to hunt on unoccupied lands outside the reservation “so long as game may be found thereon.”

“To the Tribes, this was essential — they had always moved with the seasons, following animals and accessing traditional lands for hunting, fishing and gathering,” said Davis.

In simple terms, the treaty promised that Tribal people could continue their traditional way of life even as they were confined to a reservation. For generations, that promise has been at the heart of legal battles, because states have repeatedly challenged what those rights look like today.

“The Chiefs were very wise to retain these rights,” Davis said. “The importance of that didn’t really hit me until I started writing this book.”

Ward v. Race Horse (1896) — what it means in everyday terms

While there are many significant court cases involving Indian hunting rights, Ward v. Race Horse was significant. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court case involved a Bannock man named John Race Horse Sr., who was arrested in Wyoming for hunting off the reservation without a state license.

Race Horse argued that the 1868 Treaty guaranteed his people the right to hunt on “unoccupied lands of the United States” as long as game could be found there, something his ancestors had negotiated and legally retained.

But the Supreme Court ruled against him. The Court held that once Wyoming became a state, its game laws took priority over treaty rights. In simple terms, the ruling treated treaty hunting rights as temporary and suggested they disappeared when a state joined the Union.

Davis believes this decision had devastating consequences for many Tribes, allowing states to restrict — or outright deny — rights they had previously secured through treaty agreements.

Davis said he is often asked, “Why is treaty hunting such a big deal and why don’t Indians just buy a tag like everyone else?”

“Hunting isn’t just about getting food, it’s about independence and self-reliance, providing for one’s family and passing culture and tradition down to future generations,” Davis said.

“When men were no longer able to hunt, they lost their role as providers. Prior to that, we moved with the seasons, killing and processing animals. Hunting was essential to a functioning Tribal family and community system,” he added.

Davis believes that violations of treaty promises are acts of injustice that continue to harm Indian communities, and the legacy of Ward v. Racehorse underscores the need to strengthen and support today’s tribal justice systems.

Agencies decline to discuss Indian hunting rights

In an effort to balance this article, EastIdahoNews.com contacted multiple state and federal agencies for comment on the current status and interpretation of Indian hunting rights — including the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Idaho Fish and Game, Wyoming Game and Fish, and the Bureau of Land Management offices in both Idaho and Wyoming.

Despite repeated inquiries, the agencies either declined to comment or did not respond at all. Those that did reply said they were unable to speak on the matter or deferred to other departments, which ultimately did not comment.

The lack of response highlights the continued sensitivity and unresolved tensions surrounding treaty hunting rights in the region.

Davis said he is not surprised by the agencies lack of response saying, “Everyone is scared to say anything for fear they will get in trouble or lose their job. And Fish and Game could be in litigation with some of the treaties.”

Davis believes the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) played a significant role in federal policies that ultimately harmed, controlled, and oppressed Indian communities from its earliest days.

A message for Tribal members — and non-Native hunters

Davis said he still sees many Tribal members with health disparities related to unhealthy life choices and habits and trapped in cycles of addiction and generational trauma. He hopes his book will remind his own people of where they come from — and of the strength and purpose their ancestors carried.

“We as Shoshone-Bannock people need to remember the role of family, community, duty and honor,” he said. “Life is a gift, and our families and community need us to rise and become more than we are now — physically, mentally and spiritually — for whatever challenges arise.”

He also hopes non-Native hunters and outdoor enthusiasts will learn about the history behind the Tribes’ off-reservation treaty rights and the struggles they have faced to continue practicing their hunting rights traditions on their own terms.

“There’s still a lot of ignorance around Indian hunting rights, and that’s a bad thing. We want people to understand the fight. It was the cause of war in the late 1800s — a fight for the right for us to thrive and live,” Davis said. “We’re still at war to some extent with the court systems today, which costs the Tribes time, money and perseverance.”

Ultimately, Davis believes off-reservation treaty hunting rights are not just legal concepts but expressions of identity, language, responsibility and survival.

Davis hopes his book will resonate with readers across Idaho and throughout the country, connecting themes of Tribal history, language, culture, federal Indian law and traditional hunting stories while confronting long-misunderstood truths about American history and Native rights.

Book signing and purchase information

Davis will hold a book signing and brief historical talk at Walrus and Carpenter Bookstore on Dec. 13 from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., followed by an event at the Shoshone-Bannock Tribal Library on Dec. 19. (Time to be determined). For more information, contact Taylor Akoneto at the Tribal Library in the old Fort Hall Casino at (208) 478-3919 or (208) 479-5307.

RELATED: This story begins at Walrus & Carpenter Books

For author information and updates, follow Cleve Davis on LinkedIn.

Paperback and hardback copies of “So Long As Game May Be Found Thereon…”are available for purchase on Amazon and Lulu.